آزمایشگاه و بالین

پیشگیری از سرطان

(قسمت دوم)

دکتر محسن منشدی

آزمایشگاه تشخیص طبی دکتر منشدی

آنتاگونیستهای هورمونی

داروها:

تاموکسیفن– نولوادکس رالوکسیفن- اویستا- کئوکسیفن- رالوکسیفن هیدروکلرید

طبقهبندیشده بهعنوان:

آنتاگونیستهای هورمونی

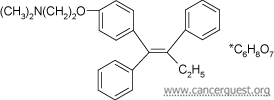

ساختمان تاموکسیفن

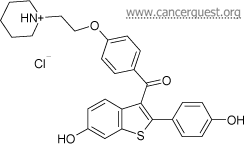

ساختمان رالوکسیفن

معرفی و پسزمینه

تاموکسیفن و رالوکسیفن، داروهای تجویزی هستند که از نظر ساختاری، به هورمون استروژن شباهت دارند. داروی تاموکسیفن در دهه 1960، در اصل بهعنوان داروی ضدبارداری تولید شد؛ اما پزشکان، پس از پی بردن به بیاثر بودن این دارو در جلوگیری از بارداری، آن را بهعنوان راهی برای مبارزه با سرطانهای تحریکشده با استروژن، مورد تحقیق و بررسی قرار دادند (69) (70). این دارو در دهه 1970 بر روی مرحله آخر سرطان پستان مورد آزمایش قرار گرفت و بهعنوان یک درمان قوی شناخته شد. در سال 1998، بهعنوان اولین عامل شیمیدرمانی برای زنان با خطر بالای سرطان پستان، تثبیت شد (70) (71).

از آنجا که تاموکسیفن و رالوکسیفن، قادر به مسدود کردن پاسخ سلولی به استروژن هستند، در دسته تنظیمکنندگان گیرنده استروژن انتخابی (SERMs) قرار میگیرند، همچنین تاموکسیفن بهعنوان عامل ایجادکننده سرطان رحم و تشکیل لختههای خونی که میتوانند منجر به انسداد عروق خونی (ترومبو آمبولی) شوند، شناخته شده است. با توجه به این عوارض جانبی منفی، پزشکان توصیه میکنند که فقط زنانی که ریسک بالایی از سرطان پستان دارند، باید از این دارو بهعنوان یک اقدام پیشگیرانه استفاده کنند (71) (72).

تحقیقات علمی

مطالعات اولیه حاکی از آن است که سرطانهای پستان تومورزا، در موشهای تحت درمان با تاموکسیفن مهار شدهاند (73). علاوه بر اثرات مثبت تاموکسیفن، مشخص شد که خطر ابتلا به سرطانهای آندومتر و رحم، افزایش یافته است. این مطلب میتواند ناشی از توانایی این دارو در تخریب DNA سلولهای سالم باشد (74). هر دو داروی تاموکسیفن و رالوکسیفن نشان دادهاند که بروز سرطان مهاجم پستان را در زنان با ریسک بالا تا حد پنجاه درصد کاهش میدهند (75) (76) (77) (78).

تأیید اداره غذا و دارو ایالات متحده

داروی تاموکسیفن در سال 1977 برای درمان سرطان پستان توسط FDA مورد تأیید قرار گرفت. پس از آن، تاموکسیفن بهعنوان راهی برای کمک به جلوگیری از عود سرطان پستان جراحی شده و همچنین جلوگیری از سرطان پستان در زنان دارای ریسک بالا تأیید شد (70). رالوکسیفن نیز توسط FDA برای پیشگیری و مبارزه با سرطان و پوکی استخوان (استئوپورزیس) مورد تأیید قرار گرفت (79) (76).

واکسنهای سرطان

پیشگیری از سرطان، هدف نهایی پژوهشگران سرطان و پزشکان است. یک راه خوب برای انجام این کار، جلوگیری از عفونت با عوامل شناختهشده موجد سرطان (ویروسها، باکتریها و انگلها) است. واکسنهایی برای پیشگیری از عفونت با ویروس هپاتیت B- عامل ایجاد سرطان کبد- و ویروس پاپیلومای انسانی،- عامل اصلی سرطان دهانه رحم و یکی از عوامل سرطانهای سر و گردن و دستگاه تناسلی مردان و زنان- تولید و مورد تأیید قرار گرفتند.

واکسنهای سرطان دهانه رحم

تولید واکسن HPV، گام مهمی در مبارزه با سرطان گردن رحم است. در حال حاضر برای پیشگیری از عفونت با HPV، دو واکسن تأئیدشده به نامهای Gardasil® و Cervarix® وجود دارند. Gardasil® دارای تأییدیه FDA برای پیشگیری از عفونت با HPV تیپهای 6، 11، 16 و 18 در خانمهای جوان در سنین 9 تا 26 سال است. FDA همچنین در 16 اکتبر 2009، واکسن Gardasil® را برای پیشگیری از زگیل تناسلی ناشی از عفونت با HPV تیپهای 6 و 11 در مردان جوان در سنین 9 تا 26 سال مورد تأیید قرار داد (80) (81). در سال 2016، CDC توصیه خود را برای سنین 11 تا 12 سالهها تغییر داد و به آنها این امکان را داد تا بهجای سه دوز واکسن HPV فقط دو دوز از آن را مصرف کنند؛ اما اشخاصی که بین سنین 15 تا 26 سالگی واکسینه شدهاند، هنوز باید سه دوز از واکسن را مصرف کنند (82).

تیپهای 16 و 18 جلوگیری میکند. استفاده از این واکسن ازHPV نیز از عفونت با Cervarix® اکتبر 2009 در ایالات متحده موردتایید قرار گرفت (83).

این نکته مهم است که واکسیناسیون یک عمل پیشگیرانه است و بهطور مؤثر جلوی پیشرفت عفونت قبلی با HPV یا دیسپلازی گردن رحم را نمیگیرد، بنابراین نباید مانع انجام تست غربالگری سالیانه توسط خانمها شد، بهویژه اینکه همه سرطانهای (انکوژنهای) حاصل از HPV در واکسن گنجانده نشدهاند (84) (85).

به دلیل پیشرفتهای هیجانانگیز اخیر در این زمینه، ما این درمان را نسبت به مابقی موارد عمیقتر بررسی میکنیم و در مورد پیشرفتهای درمانی بحث خواهیم کرد.

اعتقاد بر این است که اکثریت سرطانهای دهانه رحم توسط ویروس پاپیلوم انسانی (HPV) ایجاد میشوند. بیش از 100 واریانت (زیرگونه) HPV وجود دارد، اما فقط زیرمجموعه کوچکی مرتبط با سرطان انسان است. سابتایپهای 16 و 18 این ویروس، رایجترین واریانتهای مرتبط با سرطان گردن رحم در انسان هستند. چند ویژگی HPV باعث شده که هدف خوبی برای تولید واکسن شود؛ این ویروس، ساده و کوچک است و ژنوم پایداری دارد. در حال حاضر تولید واکسن و آزمایشات بالینی در حال انجام است.

Gardasil®

استراتژی

همانطور که در بخشهای قبل مورد بحث قرار گرفت، هدف واکسنها افزایش پاسخ سیستم ایمنی بدن به آنتیژنهای خاص است. عقیده بر این است که سیستم ایمنی بدن، در برخورد مجدد با آنتیژن پروتئینی، پاسخی بسیار قوی خواهد داد. سیستم ایمنی در مورد ویروسها، اغلب به پروتئینهای خارج از ذرات ویروسی واکنش نشان میدهد.

در شرایط آزمایشگاهی، امکان تولید ذرات غیرعفونی شبهویروس (VLPs) که شبیه به ویروسهای عفونتزا، اما فاقد DNA ویروسی و بدون توانایی تکثیر باشند، وجود دارد. این VLPs حاوی پروتئینهای ویروسی هستند و قادرند متعاقب تزریق شدن به داخل بدن، همان پاسخ ایمنی طبیعی را ایجاد کنند. دو واکسن متفاوت ویروس پاپیلومای انسانی بر پایه VLP در مرحله پیشرفته تولید و مصرف قرار دارند.

عوامل

Gardasil® اولین واکسن علیه سرطان بود که توسط سازمان غذا و داروی آمریکا تأیید شد.Gardasil® گارداسیل، بهمنظور پیشگیری از عفونت، با چهار سابتایپ ویروس پاپیلومای انسانی (6، 11، 16 و 18) طراحی شد. تیپهای 6 و 11 ویروس پاپیلومای انسانی، توأما عامل 90 درصد از موارد زگیل تناسلی هستند، درحالیکه ترکیب تیپهای 16 و 18 مسئول 70 درصد سرطان گردن رحم میباشند. گارداسیل حاوی VLPs با محتوای پروتئین کپسید هر یک از این چهار سویه HPV است.

این عامل در 8 ژوئن 2006 برای جلوگیری از سرطان گردن رحم (و زگیلهای تناسلی) در خانمهای 9 تا 26 ساله توسط FDA تأیید شد و برای اثربخشی آن بر روی سایر گروههای سنی، در ترکیب با سایر واکسنها آزمایش گردید. در 16 اکتبر 2009 گارداسیل برای استفاده مردان 9 تا 26 سال مورد تأیید قرار گرفت.

دادهها

پس از آزمایشهای بالینی مرحله اول و دوم، تعداد 12167 زن در محدوده سنی 26-16 سال، وارد مرحله سوم آزمایشهای بالینی 90 مرکز تحقیقاتی مختلف برزیل، کلمبیا، دانمارک، فنلاند، ایسلند، مکزیک، نروژ، پرو، لهستان، سنگاپور، سوئد، انگلستان و ایالات متحده شدند. از بیش از 12000 شرکتکننده، 6082 زن، سه دوز رژیم گارداسیل گرفتند درحالیکه 6075 نفر باقیمانده آنها پلاسبو دریافت کردند. این مطالعه، بروز HPV تیپهای 16 و 18 را در موارد پیشسرطانی و سرطانهای غیرتهاجمی گردن رحم، مورد ارزیابی قرار داد.

شرکتکنندگان در این مطالعه، بهطور خاص از نظر نئوپلازی اینترااپیتلیال گردن رحم (CIN) درجه متوسط (2) و درجه بالا (3) غربال شدند، CIN درجه 3 بهعنوان کارسینوم درجا نیز محسوب میشود (CIS). CIS یک پیشآگهی فوری سرطان تهاجمی سلول سنگفرشی گردن رحم میباشد. این شرکتکنندگان ازنظر بروز آدنوکارسینوم درجا (AIS) که پیشآگهی سرطان گراندولار دهانه رحم است، نیز مورد بررسی قرار گرفتند. نتایج حاصل از مطالعه نشان داد که Gardasil® صد در صد از بروز سرطانهای غیرتهاجمی و پیشسرطان با درجه بالا ناشی از عفونت با تیپهای 16 و 18 HPV، جلوگیری میکند.Gardasil® همچنین باعث کاهش خطر ابتلا به پیشسرطان با درجه بالا و سرطان غیرتهاجمی در زنانی که ممکن است پروتکل را نقض کرده و یا در خلال آزمون با این ویروس آلوده شده باشند، میگردد. این نوع درمان در تابستان 2006 موفق به دریافت تأییدیه از طرف FDA گردید (86) (87) (88) (84).

Gardasil 9®

Gardasil 9 نسخه اصلاحشده Gardasil®، برای محافظت در مقابل پنج تیپ اضافی HPV یعنی 31، 33، 45، 52 و 58 که در واکسن اصلی لحاظ نشدهاند، ساخته شد. با هدفگذاری طیف وسیعتری از تیپهای HPV، Gardasil 9 تقریباً 90 درصد از سرطانهای گردن رحم، آلت تناسلی، واژن و مقعد را تا بیش از 20 درصد نسبت بهGardasil جلوگیری میکند.

این عامل در دسامبر 2014 برای مصرف توسط دختران 26-9 ساله و پسران 15-9 ساله، از طرف FDA مورد تأیید قرار گرفت.

Cervarix®

دومین واکسن HPV، Cervarix® است که در اکتبر 2009 برای مصرف دختران 10 تا 25 ساله توسط FDA مورد تائید قرار گرفت (79). این واکسن برای حفاظت در مقابل عفونت با تیپهای 16 و 18 HPV طراحی شد، این دو سابتایپ HPV مسئول 70 درصد از موارد سرطان گردن رحم هستند. علاوه بر دو VLPs، واکسن همچنان حاوی مواد شیمیایی (هیدروکسید آلومینیوم و 3- دی آسیلیتد فسفوریل لیپید A (ASO4)) میباشد که برای افزایش پاسخ ایمنی به پروتئینهای ویروسی طراحی شده است.

فاز سوم آزمون کنترلشده با پلاسبودو سو – کورCervarix® روی بیش از 1100 زن در محدوده سنی 15 تا 25 سال، در آمریکای شمالی و برزیل انجام شد. کسانی که Cervarix® گرفتند، درست مانند کسانی که Gardasil® گرفته بودند، سه دوز واکسن در مدت شش ماه دریافت کردند. پیگیری به مدت 27 ماه انجام شد. محققان به 92 درصد اثربخشی در مقابل عفونت جدید و 100 درصد محافظت در مقابل عفونت مقاوم HPV رسیدند. نتایج همچنین نشان داد که ASO4 به واکسن کمک کرد تا یک پاسخ قویتر آنتیبادی را نسبت به زمان بروز عفونت طبیعی، برانگیزاند (89).

سرطان کبد (ویروس هپاتیت)

عفونت مزمن با ویروسهای هپاتیت، عامل اصلی خطر ایجاد سرطان کبد است. هر دو ویروس هپاتیت B (HBV) و هپاتیت C (HCV) مولد سرطان کبد هستند (90) (91). بهطورکلی عفونت با ویروس هپاتیت B، بسیار متداول است و در سال 2005 در حدود 240 میلیون نفر در سراسر جهان به آن آلوده بودند (92).

در سال 1981 واکسنی علیه هپاتیت B تأیید و بهعنوان اولین واکسن جلوگیریکننده از سرطان شناخته شد (93). امروزه در ایالات متحده، نوزادان بلافاصله پس از تولد، بهطور معمول علیه هپاتیت B واکسینه میشوند، همچنین توصیه میشود بالغین نیز علیه هپاتیت B واکسینه شوند (94) (95). برای پیشگیری از هپاتیت C هنوز هیچ واکسنی در دسترس نیست.

جداول پیشگیری از سرطان

| طبقهبندی | مواد شیمیایی |

| داروها | NSAIDs, Tamoxifen, Raloxifene |

| فیتوشیمیها | Anthocyanin,Curcumin, EGCG, Lycopene, Phytoestrogens, Pycnogenol, Resveratrol, Selenium, Vitamin E |

| روند تأثیر بیولوژیکی | مواد شیمیایی |

| آنژیوژنز | Curcumin, EGCG, Resveratrol |

| آپوپتوزیس | Anthocyanin,Curcumin, EGCG, Lycopene, Resveratrol,Selenium |

| التهاب | Anthocyanin,Pycnogenol, NSAIDs |

| متاستاز | Curcumin, NSAIDs, Vitamin E, Resveratrol |

| اکسیداسیون (برای مثال: آنتیاکسیدانها) | Anthocyanin,Curcumin, EGCG, Lycopene, Phytoestrogens, Pycnogenol |

| پرولیفراسیون | Anthocyanin,Curcumin, NSAIDs, EGCG, Selenium |

| فعالیت آنزیمی | NSAIDs |

| فعالیت هورمونی | Tamoxifen, Raloxifene |

منابع:

- Littman AJ, Beresford SA, White E: The association of dietary fat and plant foods with endometrial cancer (United States).Cancer Causes Control 12 (8): 691-702, 2001 [PUBMED]

- McCann SE, Freudenheim JL, Marshall JR, et al.: Diet in the epidemiology of endometrial cancer in western New York(United States). Cancer Causes Control 11 (10): 965-74, 2000. [PUBMED]

- Howe GR, Benito E, Castelleto R, et al.: Dietary intake of fiber and decreased risk of cancers of the colon and rectum:evidence from the combined analysis of 13 case-control studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 84 (24): 1887-96, 1992. [PUBMED]

- Morse DE, Pendrys DG, Katz RV, et al.: Food group intake and the risk of oral epithelial dysplasia in a United Statespopulation. Cancer Causes Control 11 (8): 713-20, 2000. [PUBMED]

- Buiatti E, Palli D, Decarli A, et al.: A case-control study of gastric cancer and diet in Italy: II. Association with nutrients. Int JCancer 45 (5): 896-901, 1990. [PUBMED]

6.Neuhouser ML, Patterson RE, Thornquist MD, et al.: Fruits and vegetables are associated with lower lung cancer risk onlyin the placebo arm of the beta-carotene and retinol efficacy trial (CARET). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12 (4): 350-8,2003. [PUBMED]

- Fuchs CS, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, et al.: Dietary fiber and the risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma in women. NEngl J Med 340 (3): 169-76, 1999 [PUBMED]

- Michels KB, Edward Giovannucci, Joshipura KJ, et al.: Prospective study of fruit and vegetable consumption and incidenceof colon and rectal cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst (2000) 92(21): 1740-52. [PUBMED]

- Jain MG, Rohan TE, Howe GR, et al.: A cohort study of nutritional factors and endometrial cancer. Eur J Epidemiol (2000)16 (10): 899-905. [PUBMED]

- Friedenreich CM: Physical activity and cancer prevention: from observational to intervention research. Cancer EpidemiolBiomarkersPrev 10 (4): 287-301, 2001. [PUBMED]

- Schouten LJ, Goldbohm RA, van den Brandt PA: Anthropometry, physical activity, and endometrial cancer risk: results fromthe Netherlands Cohort Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 96 (21): 1635-8, 2004. [PUBMED]

12.Vainio H, Weiderpass E. Fruit and Vegetables in Cancer Prevention. Nutrition and Cancer. (2006) 54(1):111-42 [PUBMED]

13.Greenwald P, Anderson D, Nelson SA, Taylor PR. Clinical trials of vitamin and mineral supplements for cancer prevention.Am J ClinNutr. (2007) 85(1):314S-317S. [PUBMED]

14.Boffetta P, Pershagen G, Jöckel KH, et al.: Cigar and pipe smoking and lung cancer risk: a multicenter study from Europe. JNatl Cancer Inst 91 (8): 697-701, 1999 [PUBMED]

15.Anthonisen NR, Skeans MA, Wise RA, et al.: The effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality: arandomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 142 (4): 233-9, 2005. [PUBMED]

16.Koh HK: The end of the “tobacco and cancer” century. J Natl Cancer Inst 91 (8): 660-1, 1999. [PUBMED]

17.a.b. Morimoto LM, White E, Chen Z, et al.: Obesity, body size, and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: the Women’sHealth Initiative (United States). Cancer Causes Control 13 (8): 741-51, 2002. [PUBMED]

- Bagnardi V, Blangiardo M, La Vecchia C, et al.: Alcohol consumption and the risk of cancer: a meta-analysis. Alcohol ResHealth 25 (4): 263-70, 2001[PUBMED]

- Purdie DM, Green AC: Epidemiology of endometrial cancer. Best Pract Res ClinObstetGynaecol 15 (3): 341-54, 2001 [PUBMED]

- Bergström A, Pisani P, Tenet V, et al.: Overweight as an avoidable cause of cancer in Europe. Int J Cancer 91 (3): 421-30,2001. [PUBMED]

21.Preston DS, Stern RS: Nonmelanoma cancers of the skin. N Engl J Med 327 (23): 1649-62, 1992 [PUBMED]

- English DR, Armstrong BK, Kricker A, et al.: Case-control study of sun exposure and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin.Int J Cancer 77 (3): 347-53, 1998. [PUBMED]

- Czene K, Lichtenstein P, Hemminki K. Environmental and heritable causes of cancer among 9.6 million individuals in theSwedish Family-Cancer Database. Int J Cancer 2002;99:260266 [PUBMED]

24.Lawrence H. Kushi, Tim Byers, Colleen Doyle, Elisa V. Bandera, Marji McCullough, Ted Gansler, Kimberly S. Andrews,Michael J. Thun and The American Cancer Society 2006 Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. CACancer J Clin (2006) 56; 254-281 [PUBMED]

- World Health Organization. Cancer Fact Sheet No. 297. February 2006. Accessed 2 June 2010. [http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/index.html]

- Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortaily from cancer in a prospectivelystudied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. (2003) 348: 1625-38 [PUBMED]

- Valcheva-Kuzmanova S.V., Belcheva A. Colon-available raspberry polyphenols exhibit anti-cancer effects on in vitro modelsof colon cancer. Journal of Carcinogenesis (2007) Apr 18; 6: 4 [PUBMED]

- Lin Y.G., Kunnumakkara A., et al. Curcumin Inhibits Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis in Ovarian Carcinoma by targetingthe Nuclear Factor-ºB Pathway. Clin Cancer Res 2007 13: 3423-3430 [PUBMED]

- Yanase S, Yasuda K, Ishii N: Adaptive responses to oxidative damage in three mutants of Caenorhabditiselegans (age-1,mev-1 and daf-16) that affect life span. Mech Ageing Dev. (2002) 123:1579-1587 [PUBMED]

- Missirlis F, Phillips JP, Jackle H: Cooperative action of antioxidant defense systems in Drosophila. Curr Biol. (2001)11:1272-1277 [PUBMED]

31.a.b.c.Halliwell, Barry. (May 3, 2005) Free radicals and other reactive species in disease. In: Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester http://www.els.net/[doi:10.1038/npg.els.0006101] [http://www.els.net/[doi:10.1038/npg.els.0006101]]

32.Wang, H., X. Liu, M. Long, Y. Huang, L. Zhang, R. Zhang, Y. Zheng, X. Liao, Y. Wang, Q. Liao, W. Li, Z. Tang, Q. Tong, X.Wang, F. Fang, M. R. De La Vega, Q. Ouyang, D. D. Zhang, S. Yu, and H. Zheng. “NRF2 Activation by Antioxidant

Antidiabetic Agents Accelerates Tumor Metastasis.” Science Translational Medicine 8.334 (2016). [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=NRF2+activation+by+antioxidant+antidiabetic+agents+accelerates+tumor+metastasis] [PUBMED]

33.Ramsey MR, Sharpless NE: ROS as a tumour suppressor? Nat Cell Biol. (2006) 8: 1213-1215 [PUBMED]

- Irminger-Finger I. Science of cancer and aging. J ClinOncol. 2007 May 10;25(14):1844-51 [PUBMED]

- Villarreal G, Zagorski J, Wahl Sm (January 29, 2003). Inflammation: Acute. In: ENCYCLOPEDIA OF LIFE SCIENCES. JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester [http://www.els.net/ [doi:10.1038/npg.els.0006101]]

36.Fox JG, Wang TC. Inflammation, atrophy and gastric cancer. J Clin Invest. (2007) 117: 60-9 [PUBMED]

37.Dobrovolskaia MA, Kozlov SV. Inflammation and cancer: when NF-ºB amalgamates the perilous partnership. CurrentCancer Drug Targets. (2005) 5:325-44 [PUBMED]

- de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. NatureReviews. Cancer. (2006) 6: 24-37. [PUBMED]

- MacDonald N. Cancer cachexia and targeting chronic inflammation: a unified approach to cancer treatment andpalliative/supportive care. J Support Oncol. (2007) 5(4): 157-62 [PUBMED]

- Villarreal G, Zagorski J, Wahl Sm (January 29, 2003). Inflammation: Acute. In: ENCYCLOPEDIA OF LIFE SCIENCES. JohnWiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester [http://www.els.net/ [doi:10.1038/npg.els.0006101]]

41.a.b. Baron JA, Cole BF, Sandler RS, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med (2003) 348: 891-9. [PUBMED]

42.a.b. Campbell CL, Smyth S, Nontalescot G, Steinhubl SR. Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. JAMA. (2007) 297(18): 2018-24 [PUBMED]

- Chan AT. Aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and colorectal neoplasia: future challenges in chemoprevention.Cancer Causes Control (2003) 14: 413-8 [PUBMED]

- Bertagnolli MM. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer with cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: two steps forward, one step back.Lancet Oncol. (2007) May;8(5):439-43. [PUBMED]

- Sandler RS, Halabi S, Baron JA, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas in patients with previouscolorectal cancer. N Engl J Med (2003) 348: 883-90. [PUBMED]

46.Bertagnolli MM, Eagle CJ, Zauber AG, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of sporadic colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med(2006) 355: 873-84 [PUBMED]

47.Arber N, Eagle CJ, Spicak J, et al. Celecoxib for the prevention of colorectal adenomatous polyps. N Engl J Med (2006)355: 885-95 [PUBMED]

48.Leibowitz B, Qiu W, Buchanan ME, Zou F, Vernon P, Moyer MP, Yin XM, Schoen RE, Yu J, Zhang. BID mediates selectivekilling of APC-deficient cells in intestinal tumor suppression by nonsteroidalantiinflammatory drugs. ProcNatlAcadSci U SA. 2014 Nov 18;111(46):16520-5. [PUBMED]

49.Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS. Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in relation to the expression of COX-2. N Engl JMed. (2007) 356(21): 2131-42. [PUBMED]

50.Couzin J. Drug Safety. FDA panel urges caution on many anti-inflammatory drugs. Science. (2005) 307(5713): 1183-5 [PUBMED]

51.Markowitz SD. Aspirin and colon cancer–targeting prevention? N Engl J Med. (2007) 356(21): 2195-8. [PUBMED]

- Omer ZB, Ananthakrishnan AN, Nattinger KJ, Cole EB, Lin JJ, Kong CY, Hur C. Aspirin Protects Against Barrett’sEsophagus in a Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis. ClinGastroenterolHepatol. 2012 Jul;10(7):722-7. Epub 2012 Mar

- [PUBMED]

- Baron JA. Aspirin and cancer: trials and observational studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012 Aug 22;104(16):1199-200. [PUBMED]

- Bosetti C, Gallus S, La Vecchia C. Aspirin and cancer risk: a summary review to 2007. Recent Results Cancer Res.2009;181:231-51. [PUBMED]

55.Cooper K, Squires H, Carroll C, Papaioannou D, Booth A, Logan RF, Maguire C, Hind D, Tappenden P. Chemopreventionof colorectal cancer: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2010 Jun;14(32):1-206. [PUBMED]

- Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Aspirin dose and duration of use and risk of colorectal cancer in men.Gastroenterology 2008;134:21¿28.

- Chan AT, Giovannucci EL, Meyerhardt JA, et al. Long-term use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and riskof colorectal cancer. JAMA 2005;294:914¿923.

58.Noreen F, Röösli M, Gaj P, Pietrzak J, Weis S, Urfer P, Regula J, Schär P, TruningerK.Modulation of age- and cancerassociatedDNA methylation change in the healthy colon by aspirin and lifestyle. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 Jun 28;106(7). [PUBMED]

- Cook NR, Lee IM, Gaziano JM, et al. Low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cancer: the Women¿s Health Study: arandomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;294:47¿55.

- Gann PH, Manson JE, Glynn RJ, et al. Low-dose aspirin and incidence of colorectal tumors in a randomized trial. J NatlCancer Inst 1993;85:1220¿1224.

- Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Primary prevention of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010 Jun;138(6):2029-2043.e10. [PUBMED]

- Brasky TM, Velicer CM, Kristal AR, Peters U, Potter JD, White E. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and ProstateCancer Risk in the VITamins And Lifestyle (VITAL) Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010 Oct 8. [PUBMED]

- Fowke JH, Motley SS, Smith JA Jr, Cookson MS, Concepcion R, Chang SS, Byerly S. Association of nonsteroidalanti-inflammatory drugs, prostate specific antigen and prostate volume. J Urol. 2009 May;181(5):2064-70 [PUBMED]

64.a.b.c.Takkouche B, Regueira-Méndez C, EtminanM.Breast cancer and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Oct 15;100(20):1439-47. [PUBMED]

- Zhao YS, Zhu S, Li XW, Wang F, Hu FL, Li DD, Zhang WC, Li X. Association between NSAIDs use and breast cancer risk:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009 Sep;117(1):141-50. [PUBMED]

- Bhattacharyya M, Girish GV, Ghosh R, Chakraborty S, Sinha AK. Acetyl salicyclic acid (aspirin) improves synthesis ofmaspin and lowers incidence of metastasis in breast cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2010 Oct;101(10):2105-9. [PUBMED]

67.US Food and Drug Adminstration website. Accessed 6/20/2016. [http://www.fda.gov/]

- Routine Aspirin or Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs for the Primary Prevention of Colorectal Cancer: U.S. PreventiveServices Task Force Recommendation Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007 Mar;146(5):361-364. [http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsasco.htm]

69.Jordan VC .Tamoxifen: a most unlikely pioneering medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2003) 2: 205-13 [PUBMED]

- a.b.c. Wozniak K, Kolacinska A, Blasinska-Morawiec M, Morawiec-Bajda A, Morawiec Z, Zadrozny M, Blasiak J. The DNAdamagingpotential of tamoxifen in breast cancer and normal cells. Arch Toxicol. (2007) 81(7): 519-27 [PUBMED

71.a.b. Jordan VC. SERMs: meeting the promise of multifunctional medicines. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2007) 99(5): 350-6. [PUBMED]

- Hu H, Jiang C, Ip C, Rustum YM, Lu J. Methylseleninic acid potentiates apoptosis induced by chemotherapeutic drugs inandrogen-independent prostate cancer cells. Clinical Cancer Research (2005). 11: 2379-2388. [PUBMED]

- Jordan, V. C., Allen, K. E. & Dix, C. J. Pharmacology of tamoxifen in laboratory animals. Cancer Treat. Rep. (1980) 64: 745759. [PUBMED]

74.Poirier MC, Schild LJ. The genotoxicity of tamoxifen: extent and consequences. Mutagenesis. (2003) 18: 395399 [PUBMED]

- Cuzick J, Forbes J, Edwards R, et al. First results from the International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS-I): arandomized prevention trial. Lancet. (2002) 360:81724. [PUBMED]

76.a.b. Richardson H, Johnston D, Pater J, Goss P. The National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group MAP.3 trial: an international breast cancer prevention trial. CurrOncol. (2007) 14(3): 89-96 [PUBMED]

- Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National SurgicalAdjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J NatlCancerInst (1998) 90: 1371-88 [PUBMED]

78.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breastcancer and other disease outcomesthe NSABP study of tamoxifen and raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. (2006) 295:272741. [PUBMED]

79.a.b. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves raloxifene to prevent osteoporosis. U.S. Department of Health andHuman Services. Dec 10, 1997. [http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/ANS00838.html]

80.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC); Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine:Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007 Mar23;56(RR-2):1-24. [PUBMED]

81.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. News Release: FDA Approves New Indication for Gardasil to Prevent Genital Warts in Men and Boys. October 16, 2009. [http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm187003.htm]

82.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Newsroom. Accessed 11/1/2016.

[http://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2016/p1020-hpv-shots.html]

83.Food and Drug and Administration Vaccines, Blood, & Biologics Accessed October 21st, 2009

[http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm186991.htm]

84.a.b. Food and Drug and Administration Vaccines, Blood, & Biologics Accessed October 21st, 2009 [http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm186991.htm]

85.Gardasil® Website Registered by Merck & Co., Inc. Site accessed 12/04/07 [http://www.gardasil.com/index.html]

- Lowndes CM. “Vaccines for cervical cancer.” Epidemiology and Infection. (2006) 134: 1-12. [PUBMED]

- “Merck’s investigational vaccine GARDASIL” prevented 100 percent of cervical pre-cancers and non-invasive cervicalcancers associated with HPV types 16 and 18 in new clinical study.” Merck website. Accessed 3 August 2006. [http://www.merck.com/newsroom/press_releases/research_and_development/2005_1006.html]

- Schmiedeskamp, MR and DR Kockler. “Human Papillomavirus vaccines.” 2006, The Annals of Pharmacotherapy40(7):1344-52 [PUBMED]

- Harper DM, et al. “Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirustypes 16 and 18 in young women: a randomized controlled trial.” The Lancet (2004) Nov 13; 364:1757-65. [PUBMED]

- El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012 May;142(6):12641273.e1. [PUBMED]

- Perz JF, Armstrong GL, Farrington LA, Hutin YJ, Bell BP. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virusinfections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide. J Hepatol. 2006 Oct;45(4):529-38. Epub 2006 Jun 23. [PUBMED]

- Vaccine. 2012 Mar 9;30(12):2212-9. Epub 2012 Jan 24. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: new estimates ofage-specific HBsAgseroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012 Mar 9;30(12):2212-9. Epub 2012 Jan 24. [PUBMED]

93.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. Atkinson W,Wolfe S, Hamborsky J, eds. 12th ed. Washington DC: Public Health Foundation, 2011.

http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/hepb.pdf Accessed July 20, 2011. [http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/hepb.pdf]

94.Mast EE, Margolis HS, Fiore AE, Brink EW, Goldstein ST, Wang SA, Moyer LA, Bell BP, Alter MJ; Advisory Committee onImmunization Practices (ACIP). A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virusinfection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) part 1:immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005 Dec 23;54(RR-16):1-31. [PUBMED]

95.Mast EE, Weinbaum CM, Fiore AE, Alter MJ, Bell BP, Finelli L, Rodewald LE, Douglas JM Jr, Janssen RS, Ward JW;Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Acomprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States:recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Part II: immunization of adults. MMWRRecomm Rep. 2006 Dec 8;55(RR-16):1-33; quiz CE1-4. [PUBMED]

ارتباط سرطان سر و گردن با ویروس پاپیلوما

برای دانلود فایل pdf بر روی لینک زیر کلیک کنید

ورود / ثبت نام